Persian / Dari version of the following text - فارسی

Education Equals Freedom

In a world where at least 40% of all inhabitants are entrenched in poverty, it is education that will make a difference. Will we have a future where we can solve problems and create value, or one where we dig an ever-deeper hole for ourselves with poverty and crime? Education holds the answer.

The Answer is Education

According to the World Bank, a staggering 648 million people struggle to survive on less than $2.15 per day (World Bank 2022). That’s a meager 215 pennies—or even less—to pay for food, shelter, health care, and all other basic needs. Nearly half the world’s population lives on less than $5.50 a day. (World Bank 2018).

Even in one of the most affluent societies in history, the United States, one of every nine citizens live in dire poverty. For some American minority groups, the poverty rate is even higher—one in six Hispanics and one in five Blacks (Census Bureau 2021). Far greater numbers struggle to make ends meet. According to one study, 42% of American households are “asset limited, income constrained, yet employed.” They find it difficult to afford “basic necessities of housing, childcare, food, transportation, health care, a smartphone plan, and taxes” (ALICE 2022).

Surely, we can do far better. We need to work towards a more secure future for our children and grandchildren. What is the answer?

One school of political thought blames the victim, insisting that if a person—or a nation—doesn’t succeed, it’s their own fault. Another theory holds that the government can break the cycle of poverty by taxing the wealthy and giving the money to the poor. The equivalent theory in international relations is that the cycle of poverty in developing nations could be broken if only enough foreign aid money were available. The truth is plain, however, after many generations of social experiments: neither approach works. They fail to achieve long-term solutions to poverty because they neglect to give people the tools required to make permanent improvements to their standard of living. The answer does not lie on either end of the political spectrum.

The answer is education.

In the words of Nelson Mandela, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” It unleashes the creative potential of a society to face its challenges through innovation, problem-solving and constructive change. It can provide a person with a way out of poverty by training them to think critically, communicate persuasively, and collaborate effectively. Education can and should provide them with the skills they need to create prosperous lives for themselves, their families, and their communities.

Reform is Needed

Earth’s nations already invest enormous resources in education, to the tune of $4.7 trillion per year (UNESCO 2019). In the United States alone, $800 billion is spent each year on public elementary and secondary schools. That’s $15,621 per public school pupil, a level that has increased steadily over the past decade. At the beginning of the 20th century, the US spent only about 1% of its GDP on education. By 2017, that figure had risen to 6.1% (National Center for Education Statistics 2022). These trends are clearly visible from a global perspective. Many nations spend 6-8% of their GDP on education.

Similarly, the world devotes prodigious amounts of human capital to education. In the US, there are 3.0 million teachers in K-12 public schools and another half million in private schools (National Center for Education Statistics 2020). They are highly educated and credentialled. The large majority are dedicated and passionate about what they do. Many serve under difficult, even hazardous, circumstances. Some of their efforts are heroic.

Yet despite these enormous investments, America languishes far behind many other developed nations in standardized assessments of student achievement. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), for example, ranked students from 77 countries on scholastic performance in mathematics, science, and reading. The US found itself in 25th place, far behind top-ranked China. In mathematics, the results were even more disheartening. American students ranked in in the middle of the pack at 37th place, just ahead of Malta and Belarus. But the news was alarming for many countries. Scores have been steadily—and in some cases, sharply—declining over the last two decades in Korea, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, Finland, and Sweden. Students in the 118 nations of the world are unranked. Most are presumably struggling to meet performance standards (PISA 2019).

Clearly, most of the world’s educational systems are not providing an adequate return on investment as measured by student learning. Children from developing nations and from socioeconomically disadvantaged ethnic groups within wealthier nations are especially affected (National Center for Education Statistics 2019). Reform is needed.

Simply pouring more resources into the existing system will provide only marginal improvements at best. America, for example, spends about $200,000 educating an average student from kindergarten through 12th grade in public schools. This level of financing is already hopelessly out of reach for most nations. Keep in mind that half the world’s children subsist on less than $2000 per year for all their living expenses. How can their communities be expected to spend 100 times that amount providing them with twelve years of public education?

Yet we’ve seen that for all its wealth, American students ranked only 25th in the world in academic achievement. According to a recent study, increasing funding by 10%--in other words, spending an additional $20,000 on each student—would result in only small benefits. This increased spending would only lead to “0.31 more completed years of education, about 7% higher wages, and a 3.2 percentage point reduction in the annual incidence of adult poverty” (Jackson 2015).

Any change that can nudge educational and life outcomes in the right direction is encouraging. But we must be honest with ourselves: for the tens of millions of Americans who experience financial insecurity or outright poverty, these small improvements aren’t nearly enough. Even this level of increased investment would be difficult for many American communities to sustain. It would be far beyond the capacity of billions of the world’s inhabitants whose needs are already the greatest. The only realistic hope, then, is to explore new models for education.

At first glance, schools in the 2020s may seem radically different than their counterparts in the 1920s. Some changes are highly significant: Many school systems are far more racially and culturally integrated than a century ago. Other changes simply reflect the ongoing technological revolution in wealthier nations: Textbooks, chalkboards, and class notes are being replaced by eBooks, digital slideshows, and websites.

But these improvements and innovations are by and large only layered on top of an antiquated model. Education is still mostly a matter of a teacher dispensing information to students who are expected to remember it and repeat it back during examinations. The lecture-discussion format still predominates. “Labs,” when they exist at all, are normally only demonstrations. They are rarely opportunities for exploration and discovery. While the best teachers usually try to assess higher-level thinking in exams, tests still mostly measure rote memorization. In many countries, a significant portion of the school term is spent coaching students on how to score well on standardized achievement tests. Sadly, unless they take special electives in art or shop, students likely graduate without producing anything of lasting value. Only a vanishingly small number have any experience applying what they’ve learned to solve real-world problems.

In short, the 2020s are to a large degree merely a digital version of the analog 1920s. It’s time to change the paradigm.

The Organic Educational Ecosystem

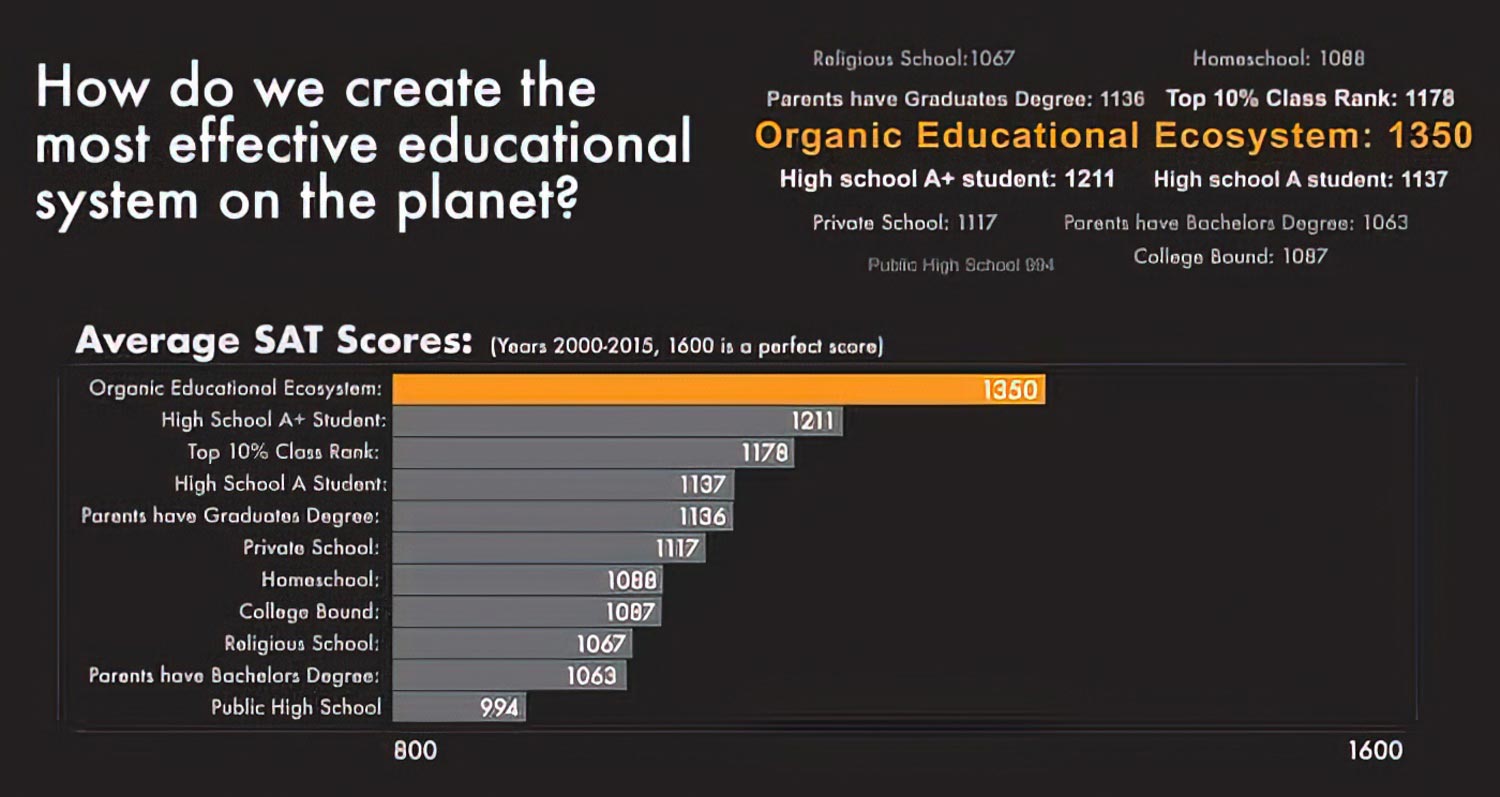

A dynamic new approach to education has emerged and proven itself over the last two decades. The measurable outcomes far surpass the results achieved by the conventional but outdated classroom model that dominates both public and private schools worldwide and that has been transplanted almost intact into most homeschooling efforts in the United States and elsewhere. The results aren’t even very close (Figure 2 below).

This approach challenges students not to learn information or study “subjects” for their own sake, but instead to discover knowledge and apply it collaboratively, always looking to develop creative solutions to real-world problems. To borrow the words of the Greek historian Plutarch, this approach regards the mind as “not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.”

How can this new model achieve such dramatic results without requiring the influx of massive—and frequently unavailable—new financial resources? It succeeds by following several fundamental principles. Under this modern approach, education is:

Daily

In many nations, classes are typically conducted five days a week for about nine months each year. After a long summer break, classes reconvene in the fall. The first several weeks of the new term are spent trying to relearn material covered during the previous school year. Education is a “two steps forward, one step back” phenomenon. The learn-forget-relearn cycle is repeated on a smaller scale over the winter and spring breaks—and in fact over every weekend during the term. In contrast, with the new approach students learn, assimilate, and apply knowledge daily.

Collaborative

In the real world, success is highly dependent on our ability to work with others. Under the traditional classroom model, instruction is a highly individualistic affair, even if a large group is gathered in a single room. Music, drama, and athletics are notable exceptions. But for the core subjects, students are mostly expected to learn by listening to a teacher or (in the older grades) by reading a text in “study hall.” Then they are supposed to solidify their learning by spending an average of 6.8 hours per week on homework, often with only minimal parental involvement (National Center for Educational Statistics 2012). Most educators recognize the value of collaboration on some level. They pair students up as lab partners. They require students to work together on assignments in math or some other subject during class on a few days each term. Nearly always, however, these group assignments could just as easily have been accomplished by individuals working alone. One fundamental difference with the new approach is that learning is viewed as primarily a journey you undertake with others—and not necessarily just those of your own age group.

Team-Based

It makes sense, then, that teams of learners working together should be the rule, not the exception. Again, this principle reflects the real world, where every successful business or arts organization relies heavily on teamwork. It can also be found in many pursuits at the highest levels of academia. Look at a research paper in any scientific discipline. The authorship line typically has four to eight names. Sometimes, there are dozens. That’s because university research labs are always comprised of teams of people at various stages of their careers—undergrads, grad students, postdocs, and professors. And if you check out the byline in that science journal article a little more closely, you’ll often see that teams cross institutional lines, mixing researchers from academia, industry, and government institutes. You will discover the same thing if you examine elite post-graduate training programs in design and other fields. But why should students wait decades to experience the power of a team-based education? The new paradigm described here incorporates team learning—and team doing—from the beginning.

Project-Based

Learning requires doing. We know this instinctively. It’s impossible to learn to play basketball, for example, by studying the rules and history of the sport and watching games on television. It requires countless hours of practicing dribbling, passing, and shooting with an actual ball in your hands—and then refining your skills in competition against real opponents. Similarly, cooking can’t be learned by reading textbooks or watching Food Network. It requires getting into the kitchen. In the work world, countless college graduates can testify that they didn’t really begin to learn their field until they were assigned to a project and had to do something. It’s strange, then, that so much of the conventional educational model involves putting students at desks while they listen to verbal instruction. As astronomer Neil deGrasse Tyson observes, “We spend the first year of a child’s life teaching it to walk and talk and the rest of its life to shut up and sit down. There’s something wrong there.” The new educational model that we are describing instead incorporates project-based learning as a fundamental principle.

Case Study Based

In the conventional paradigm, there is a tension between general education and specialization. In grades K-12, education is often broad but shallow. In university graduate schools, it is often deep but very narrow. As the joke goes, general education can be “learning less and less about more and more, until you know nothing about everything,” while specialization can be “learning more and more about less and less, until you know everything about nothing.” The problem is that neither extreme does an adequate job of preparing students to accomplish meaningful tasks in the real world. That is why the new paradigm emphasizes the case study as a fundamental component of learning. The case study focuses on a single, well-defined problem that must be solved in real life. There usually isn’t one “right answer.” Instead, a range of competing needs and potential approaches must be weighed to come up with a workable solution. For example, the case study could involve redeveloping an industrial area near a city’s downtown. Alternatively, it could focus on taking a novel idea all the way from conception to marketing. Or it could look deeply at a specific event—how a history-changing battle was won, or how a garage-based startup eventually disrupted an entire industry. Many disciplines—economics, logistics, politics, and law, to name a few—are brought to bear on an actual problem, just as they must be in real life. A case study done right will be far beyond the ability of individuals to accomplish alone. It will require collaborative, team-based learning.

Community Engaged

In most conventional educational settings, learning takes place primarily in the classroom, and the teacher is expected to be the subject matter expert who dispenses information to students. The community is rarely involved on a meaningful level. One exception is the science fair, where outside experts usually volunteer to evaluate the projects and select the winners. Imagine a scenario where knowledgeable members from the community routinely are involved in mentoring, guiding, and evaluating students in their learning, regardless of the topic. Educators would be less of a “one-person band” and more of an orchestra conductor. In an orchestra, conductors don’t try to play all the instruments themselves. Instead, they are responsible for bringing out the expertise of a community of virtuoso musicians to perform a symphony. Community experts have limited time, of course. They are busy people. But many have altruistic motives, and they genuinely enjoy sharing their knowledge and experience with others. Some have children of their own and would feel a responsibility to give back, if they knew how. Others may regard involvement as a valuable way to groom and recruit future talent. Recorded media such as “Ted Talks” may fill some of the need, but direct interaction makes a huge difference. It will require students to learn the skills needed to compose meaningful written correspondence or engage in video calls. It may involve classroom visits or field trips. It will certainly require engagement outside normal hours—another reason why the “daily” aspect of the new model is so important. It’s work. But the power of community involvement in a team-based, project-based education cannot be overestimated.

Entrepreneurial

The current paradigm trains students to be consumers rather than producers. Students regularly consume “school supplies,” textbooks, and instructor-prepared content, but rarely do they produce anything. Once again, music, shop, the arts, and athletics are the main exceptions. Only under the rarest of circumstances would the core curriculum generate any tangible object or business or invention for the benefit of students and their families, let alone for good the community at large. But should that outcome be too much to ask from education? In their adult lives, students will be expected to contribute something of value in return for their livelihoods. They need more than typical vocational training. In the modern world, entire categories of employment opportunities that existed for previous generations are being taken over by AI-driven machines. Since 80% of all jobs will not exist ten years from now, and the skills for the new jobs of ten years from now cannot yet be taught (Harvard GSD, “Smart Cities”), you see the problem. We are doing a disservice to our young people if we somehow do not equip them to innovate, to solve problems, to create value, to add something new and unexpected. That is why the new paradigm we are discussing is entrepreneurial at its heart. Not every student project will generate an invention or create a new business, although some will. But students will continually be challenged to develop an entrepreneurial mindset. They will constantly make connections between what they are learning and the problems and needs they see around them. If they learn something new, they will look for a problem to solve with that skill. If they see a need, they will ask themselves what they already know and what they must learn so they can meet the need. Students trained in this mindset will become solution-oriented, adaptable, and anti-fragile (MIT Sloan 2022). They will learn to be determined, focused, authentic, and creative (University of Arizona 2022).

Summary

The new paradigm aims to create an organic ecosystem of education. In the natural realm, an ecosystem is an interconnected community of organisms and their physical environment, where everything interacts to sustain life and foster growth. In the realm of education, members of the community are interconnected to nurture creativity and practical know-how in both children and adults. This approach is more than theory. Where it has been put into practice, it has generated some spectacular results.

Rockin’ the Schoolhouse

How do we harvest the full potential of every child regardless of their parents’ education or wealth or their teachers’ credentialing, whatever their IQ or natural abilities, wherever they happen to live? And how can we achieve this goal without requiring any major expense or relocation?

That it can be done has been demonstrated where it counts: in the real world with real children.

The top college-bound students in the world achieve a Harvard-level SAT score (1505) only 4.3% of the time. By comparison, 31% reach this lofty standard in the Organic Educational Ecosystem (Figure 2). To put it another way, students educated under this new paradigm are 700% more likely to achieve this astronomical score. This level of accomplishment exceeds every PISA international success story as well.

Figure 2. Results of the Organic Educational Ecosystem Experiment (2000-2015).

With all data points verified, the likelihood of the Organic Ecosystem SAT scores being randomly selected from the college-bound population of American students is less than 1 in 500 billion and from the private school population less than 1 in 2 billion. This is not even a fair fight.

Certainly, the teachers and students in every existing educational system are dedicated and sincere. We simply haven’t given them the right tools for the task. It’s as if we provided our children and their teachers a shovel and a faulty set of instructions and asked them to perform a heart transplant! We’re primarily still using Industrial Age concepts from the late 19th and 20th centuries. In the 21st century, we must instead focus on advancing intellectual and creativity platforms. The tools and methods matter. It’s not difficult to measure and compare, thankfully.

Let’s consider another angle. We’ve already discussed the cost of public education to the economy. Recall that the amount spent on education worldwide is $4.7 trillion per year (UNESCO 2019). Depending on the country, that amounts to somewhere between $3,000 and $19,000 per student annually. This figure represents as much as 6-8% of any nation’s GDP. This investment often yields only a very low chance of a Harvard SAT level of success. What if we could achieve better results with money to spare, and resources we could reallocate towards alleviating poverty and improving critical infrastructure?

Are private schools the answer? In exchange for tuition of perhaps $40,000 per year in many private schools in western nations, the same students will have purchased a mere 120 SAT points with their family’s money. So, someone might say, we could save that $40,000 by making time to “home school” the children. If we pretend that most people have the time, they might indeed save some money initially, perhaps even enough to make up for any forfeited income. But the statistics don’t bear out the claim that homeschooling is a superior form of education compared to those “high student-teacher ratio, one-size-fits-all” public or private schools. You would lose, not gain, 29 SAT points by eschewing those expensive organized schools, while perhaps depriving some young people of the opportunity to develop the necessary social skills for college, career, and family.

So then, go ahead and become an A+ student in a public or private school, if you can…and you’ll be joining an elite group that still averages 300 points below a Harvard-level 1505 score. Besides, it’s an open secret that an A+ is not what it used to be. In 1990, the average high school GPA was 2.68. A decade later, it had risen to 2.94 (National Center for Education Statistics 2004). By 2016, it had risen to 3.38. Now, nearly half of all students (47%) graduate with an A average (Hurwitz and Lee 2018). Meanwhile, SAT and ACT scores have not kept pace with this rampant grade inflation, and a disheartening proportion of these students fail to earn a degree within six years after starting college. Perhaps the graduation rates and grading standards are influenced by the desire for federal or state financial rewards, teacher tenure, and community accolades?

Will you consider, then, daring to spearhead an Organic Educational Ecosystem? Will you see the SAT scores skyrocket to nearly one out of three achieving this Harvard-level of success, as documented over 15 years of this journey, this “experiment” of life? Keep in mind that these SAT scores were a byproduct of the educational experience, not a goal. The students achieved these results entirely without emphasis on earning high college entrance exam scores and without diverting time to test preparation. Instead, more emphasis was placed on frequently neglected elements like sports, computer coding, music and the arts, while developing a surprising and dazzling social acumen for the great journey ahead. Many professors, interviewers, and employers have expressed strong confirmation of these points both publicly and privately when evaluating students who experienced the Organic Educational Ecosystem.

Skeptical? Then follow this same statistically relevant sample set into their careers. You will discover that their average salaries are between 300% and 800% higher than those of their Millennial peers. The student with the lowest SAT in the 15-year Organic Ecosystem experiment proceeded to land a job that paid 360% of the average Millennial salary in his region.

These results cannot be explained away as “accidental” any more than flipping a coin in a Bernoulli Trial and observing it landing on its edge five consecutive times could be accidental. Something’s up.

Must it be a genetically advantaged sample set of students? Or maybe the parents all have advanced degrees and a lot of spare time on their hands to invest in the young students? Ah, but here are the facts: only 41% of the parents graduated from college, 35% dropped out of college, 24% never attempted college, and several were High School dropouts in their day.

Wow.

An eye-opening 80% of the students in the Organic Educational Ecosystem surpassed their top-performing parent in every socioeconomic category. This value stands in sharp contrast to the struggles that most Millennials face. In 2016, the average wealth of Americans between the ages of 23 and 38 was 41% less than their counterparts enjoyed in 1989 (New America 2019). Further, Millennials “are also more likely to be living at home with their parents, and for longer stretches” than previous generations (Pew Research 2019). Nearly all of today’s 30-year-olds in the Organic Educational group surpass their parents’ wage at age 30. It is not statistically possible that this is an accident.

Why did this happen? And how?

A Light Bulb Moment

In 1986, at a Parent-Teachers night for first graders, the sight of the bulletin boards in the classroom produced a light bulb moment. The lights came on, that is, just after the sight delivered a feeling like a punch to the solar plexus. The factory-like techniques being employed, even by the highly trained and sincere teacher, could only be expected to dumb down students.

This educational model was obviously a throwback to the days when Henry Ford and the Industrialists needed millions of assembly line workers. They knew that “Education Equals Freedom,” so they borrowed from Europe and reinvented a means of gearing schools to turn out a contented workforce. Factory owners could not expect inspired, creative men and women to perform repetitive tasks for 10 hours per day without rebelling. To solve this problem, the factory-model school was created, complete with yellow factory buses taking innocent and potentially brilliant sponges to their destinies year after year. Average-level, topic-segregated material was imparted by lecture format to age-segregated children, whose social and moral value training was provided mostly by their peers. In practice, students were required to repeat back that topic-segregated information to the teacher on a test to achieve “success.” Students like the young Albert Einstein never quite adjusted themselves to that paradigm, thankfully.

Of course, there have always been extraordinary teachers who broke the rules and defied the mold. Indeed, the top 10% of teachers convey three times more information than the bottom 10% (Economist 2016). What, then, happens to 90% of our students? Most are mired in a system where they do not “learn how to learn,” but merely repeat what they’ve been told to repeat. The conventional paradigm does not reward thought or creativity. It is a high-stakes game of Simon Says.

Teachers are generally underpaid. Valued against their contributions to the future of our nations and neighborhoods, one can argue that they are severely underpaid. For many, the stress of the profession, exacerbated by chronic staffing shortages, is taking a heavy emotional toll. As of 2022, a sobering 55% of teachers were considering leaving the field (NEA 2022). But schools must allocate their resources to more than just staffing. Their legacy brick-and-mortar buildings must be maintained, and their carbon footprint infrastructure problems must be addressed. Buses and other vehicles must likewise be fueled, serviced, and periodically replaced. As we have seen, this capital investment is a massive burden. Constructing a school cannot be repeated more frequently than once per generation in any given locale.

Money is not really the issue, however. As we have seen, investing more money delivers only a marginal impact on results. Clearly, then, too much money is already misspent, even with the best of intentions. Providing more funding for orphanages is a good plan in theory, but dollars and cents will never replace the value of a healthy family under any circumstances. There is an intrinsic heartbeat in a family that cannot be bought. The same is true regarding our current topic, education. The problems cannot be addressed with increased funding alone.

We must teach the next generation to learn how to learn together with others, not how to recite remembered information. If they are to succeed, today’s young people must be able to reeducate themselves every 18 months for the rest of their lives. Above all else, we must teach that skill in the context of relationships, not programs. That is the lesson of the Organic Educational Ecosystem.

What is this new paradigm, where students can graduate with a high-quality university Engineering degree and already be well into a master’s degree program before they reach their twentieth birthday? How do three students share the Physics Award of a 29,000-student university—the first time in the school’s history a tie was recognized—and all three come from this Organic Ecosystem? None of the three were even Physics or Engineering majors when they excelled in their classes and earned their awards. What are the odds? The Organic Ecosystem has produced many students who have received full-ride scholarships, have been named valedictorians in language or science or liberal arts, and have received accolades and promotions at an early stage in their subsequent careers. Those of us who were involved never even gave it much thought at the time. It all came naturally, it seemed.

Don’t these results sound rather like the incredible success stories of America’s “founding fathers” 250 years ago? Often at a very young age, these normal people excelled in calculus and higher mathematics, science, technological innovation, medicine, law, military strategy and leadership, business, philosophy, and the arts. No fewer than half of these “founding fathers” were self-educated or had studied under mentors. Many never saw a day of college.

“The coin has landed on its edge, five times in a row.” But it’s all happened before. We are merely rediscovering the rhythm of a new, but ancient, music.

The Guiding Principles

Can the Organic Educational Ecosystem still be implemented if an entire infrastructure is already in place? Yes. The preexisting buildings and professional teachers can play a vital part. We hope to expand the pool of educators, not shrink it. The more the merrier! Any attitude of elitism needs to be jettisoned, certainly, and the concept of a teacher who dispenses information must give way to that of a facilitator who opens doors and windows into the future. Likewise, the factory-like school setting needs a total makeover. Its rows and files must be transformed into circles and clusters of students working together. We anticipate that teachers’ morale and job satisfaction will skyrocket as they enjoy increased community involvement and parental support and as they experience the freedom and excitement of learning alongside their students.

Specific techniques for implementation will necessarily be fluid. Yet there are guiding principles that have led to staggeringly positive results wherever they have been followed. Do you dream of an environment where not even a single student falls through the cracks, where young people are instead propelled into early career advancement that will mean millions of dollars of additional income to their families over the course of their lives? Let’s have the courage to do more than incrementally tweak the current system. Let’s be daring in following these principles now that they have been tested for more than a generation.

Character matters

The households that were engaged in this audaciously simple educational journey did not belong to any religious organization or attend any scheduled religious meetings. Still, nearly every parent expressed great seriousness about knowing and living the teachings of Jesus, who is recognized by every major world religion and most secular historians as, at minimum, a great Man. Why does this fact matter? Practically, this priority of life seems to translate into character qualities of work ethic, honesty, peace, respect for authority, curiosity, creativity, and care for peers of differing ages or races.

Impart Life, not “subjects”

Conventional practice divides learning into disconnected topics called “subjects” and assigns them to specific time slots, curriculum plans, and age groups. If we do that, we lose. What is mathematics, really? It’s music, it’s material science, it’s physics, it’s biology and chemistry, it’s sports, it’s computer science and programming, it’s full-duplex nanotechnology radio frequency CMOS circuits, it’s rocket propulsion, it’s carpentry, it’s finance, it’s culinary arts…and so much more. Know that mathematics encompasses all of life. Feel it. Impart it. Discover it together. Wow! That realization frees us from pressure even as it fills us with wonder. What is art? What is Phys Ed? What is a weekend or a vacation? What are literature, grammar, writing, reading, earth science, and history? They are all mingled together if we experience and impart life correctly. And naturally, the truth of life’s interconnectedness is embedded in every form of great leadership.

Be collaborative

Your job isn’t really to teach—it’s to facilitate “learning how to learn.” For example, gather everyone on couches or around tables. Make some laptops, tablets, or smartphones available. Ask them what has interested them that day. A building under construction? Great! Let’s dive in. What’s the building made of? How does it stand up? How much will it cost? Who is paying the bill, and why? What will be inside? Will the building be leased? What is a lease, anyway, and how will the tenants pay for it? How are water and heat supplied? Who pays for these utilities, and how is the required energy created? Are the building’s skin and bones, arteries, and lungs built using old technology or new? Can you come up with ways to improve the design or to use better materials? Think. Imagine! Perhaps the next multibillion-dollar industry will emerge from the brainstorming taking place on that couch. This is not the industrial revolution any longer, when only the elite and privileged can own the future. Research together. Answer together. There are no experts needed to get started, and no one who cares can fail. No explorer left behind!

Moving Forward

A new generation of thinkers and entrepreneurs and geniuses is on the way. They are learning to kick a ball like Pelé and play the piano like Krystian Zimmerman, in between and during discussions about coefficient of restitution, tensile strength, and dozens of other interrelated topics. The good news is this: we don’t have to know a thing to serve as facilitators. We simply need the will to discover how to learn together—researching, brainstorming, traveling, and interviewing knowledgeable people. We facilitate and mentor as “we rise up and sit down and walk along the way,” with no regard to arbitrarily defined subjects, time periods, or academic calendars. Life is a field trip, the older facilitating the younger (with more questions than answers) and the young returning the favor. In this way, we will never be “the cork in the bottle” for those who follow behind us—but rather the fuse that ignites their futures.

Gather interested neighbors and friends to help facilitate learning how to learn. Different adults can take responsibility for a block of time during a day or an evening, depending on work and travel schedules. All invest as they are able. This process, reaching across age groups and economic strata, obliterates the race and educational distinctions that dominate a typical school or workplace environment. Twenty-plus years of experience bear out that a twelve-year-old can find their “best friend” to be a forty-year-old or a nine-year-old over time. Consider what this mentorship, apprenticeship, and internship can do for a young child’s ability to think and communicate with a wisdom and maturity far beyond their years. It’s rewarding—and a whole lot of fun.

A Practical Discussion

The narrative so far has focused on the rationale behind the Organic Educational Ecosystem and the principles that undergird it. We have not tried to provide a User Manual with detailed procedures and protocols. That omission is intentional. For one thing, these principles will need to be implemented in a highly diverse set of circumstances found among various families, communities, and nations. For another, the very nature of an “organic” system is that it develops from within rather than being imposed from without. We want readers to focus on catching the vision rather than following an exact template. Still, organic life is not a free-for-all. Pragmatic, workable solutions are available.

Worth Your Time

A lengthy, practical discussion about the Organic Educational Ecosystem was captured recently as a group of parents and friends talked through some of the details in a real-life setting. If you are interested in reading a transcript of this conversation, we invite you to do so.

College, Continuing Education, and Beyond

A college education is an expensive proposition. The average tuition for a four-year public university in the United States is $10,740 annually for in-state students and $27,560 for out-of-state students (CollegeBoard 2021). The average tuition at private universities tops $38,000. Tuition is only one consideration. The average room and board cost for a year of public education is $11,950 and for private education is $13,620. And then there is the opportunity cost. Students are spending money in school rather than earning it in the workforce. For those who most need the socioeconomic advancement promised by a college education, it is prohibitively expensive, excessively time-consuming, and geographically challenging.

Unlike 25 years ago, in our day anyone with an affordable broadband connection can access high-caliber educational materials through Harvard, MIT, Coursera, Khan Academy, Great Courses, and many other platforms, all without requiring any travel. As has been discussed, the quality of the instructor is essential to a student’s success (Economist 2016). Unfortunately, the best educators will usually be unwilling or unable to live in the communities that need them the most. However, for the first time in human history, the top 10% of the world’s teachers can appear daily in the homes of every child and adult on the planet, providing top tier education in any world language at an extremely low cost.

With such a vast array of universities providing access to exceptional academic coursework, the only missing ingredient is the opportunity to earn a recognized college degree. In the educational system that took shape by the 1600s, there was a certificate of completion that became known universally as a “degree.” And yet, in the new technology world of the 21st century, this verifiable certificate of completion—often required for job application or entrance to other university programs—is dated and expensive. The educational experience it documents is “low density,” since social and political distractions are infused into the college experience. In our technological age, what alternatives can we envision for the dated “you have to have a degree” requirement we’ve inherited from past centuries?

Consider one alternative: certification. By attending a week-long conference or taking coursework specific to a particular industry, you can receive a certificate in one thing or another. Well-known examples include Microsoft or Google Analytics certification. This kind of credential has genuine, tangible value within a narrow scope. It allows the trainee to qualify for a certain group of jobs.

Let’s consider how to build on the certification model. It is possible for the first time ever to bring upper-echelon instructors into every home on the planet. What is lacking is a way for people who want to improve their lives to leverage this opportunity into credentialling that will gain the respect of a job recruiter or interviewer. To do so, people first need inexpensive, preferably free, access to the internet. Next, they need guidance to select appropriate education that will help them achieve their career goals. Finally, they need tangible evidence that they have completed a course of education under top instructors from respected universities and have become proficient in a valuable skill. It must be more than an unverifiable claim.

Unless we provide them with a goal and a roadmap showing how to reach it, most people will likely squander the opportunity afforded by internet access, spending it on Netflix or social media rather than using it for educational advancement. Without receiving guidance and the hope of reward, many will find themselves wandering in the wilderness of life.

That’s the rationale behind the Presidential Intellectual Fitness Award. It hopes to provide the tools, guidance, and mentoring required to fill this desperate need. The Presidential IF Award can provide an accredited pathway to inexpensive but high-value education and mentoring.

We hope to take the best from existing educational systems and methodologies, whether from public, private, charter, or homeschools. We want to add the concepts of mentorship and apprenticeship. We will upgrade with modern technologies. We will bring these factors together to create an Organic Educational Ecosystem experience for adults, regardless of their nationality or class or background.

There are many highly successful people from the manufacturing, technology, and service sectors who are looking for ways to give back to society. The Presidential IF Award system of facilitated collaborative discovery builds relationships with educators, mentors, and employers. These relationships generate opportunities for internships and good jobs, whether for young learners, for adults in the workforce who wish to improve life for themselves and their families, or for returning citizens who need a chance at a fresh start.

Students and their families could join industry and community leaders for backyard barbecues, sporting events, cultural happenings, and recreational outings. When lives and stories are shared, the unintentional—but nevertheless ubiquitous—barriers separating social strata are broken down. The newly formed relationships will become the building blocks of life and success. Intentional creation of diverse, strata-busting relationships can make a far greater impact on students’ success outcomes than any government mandate or subsidy could hope to accomplish. Research proves that nothing fights poverty like strata-defying friendships (New York Times 2022; Nature 2022).

And while sitting people in the row-and-file, lecture-and-repeat environment of “factory education” may be enough to create assembly line workers, as it was designed to do, it can never foster the kind of true relationships that break down barriers.

In this generation, we know better, and we can do better than that. Don’t we have a moral obligation to act?

Consider this: five percent of every community is blessed with brilliant intellectual capacity, regardless of their wealth or social status or educational background. There are oceans of humanity who have no access to university education and credentialing or to the job opportunities that require them. The gifted five percent in those communities might be able to contribute a cure for cancer, a fix for water shortages, or a game-changing way to clean up the environment. But unless we are willing to alter our approach to education, they will never have a chance. Instead of changing the world for the better through their genius and creativity in science, technology, music, or art, they will die young due to crime or poverty or disease.

Let’s act decisively! We have an unprecedented opportunity. We now have the tools to find and equip those human resources. We can provide the underserved or vulnerable with free broadband access and connect them with world-class educators in a mentored and collaborative creative environment. We can award their accomplishments with universally recognized and verifiable Presidential Intellectual Fitness Award credentialling that will provide them with access to good-paying jobs and additional education and training. We can incorporate all of that into a relationship-based incubator of mentoring, internship, and apprenticeship.

Again, isn’t it our moral obligation to connect the millions of neglected but brilliant minds in the United States—and the hundreds of millions throughout the world—to top-tier educators? And isn’t this our best chance to head off an avalanche of issues with energy security, social cohesion, crime and justice, environmental decay, inadequate housing, and shortages of healthy food and clean water?

Presidential IF Award system Summary

For those under the 50% of Average Median Income (AMI), comprising Americans in the lowest quartile of family income, we will provide:

- Free Gigabit Wi-Fi

- A registered device

- Free login credentials for that device

We will also create a path for success through the Presidential Intellectual Fitness Award. It will provide a flow of coursework that results in accreditations based on achievement levels corresponding to set standards. These achievement levels will adopt the martial arts belt model—beginning at white belt and advancing all the way to black belt—that has already proven successful in Six Sigma and other certification programs.

Successful members of the community will donate three hours a week of their time to people enrolled in the Presidential Intellectual Fitness Award program—going into public schools, providing tutoring, or interacting with groups of people in their community. Mentors will direct and encourage those in the program so that no one who cares is left behind. These relationships will provide inroads to the community’s commerce and industry and technology worlds. Job recommendations and internships can flow naturally out of these relationships.

So, the keys for rising to new heights will include:

- Direction and guidance through coursework packages

- Levels of Achievement at every stage, corresponding to martial arts belts

- White House approved accreditations based on mastering various coursework packages

- Availability of mentors for change

What would happen if everyone was given a chance? Let’s find out together!

Michael Peters

Washington, DC 20003

202.802.8072

LinkedIn profile and contact

Videos

Education Equals Freedom for Nations from Poverty and Crime

Gigabit Wi-Fi - The Fishing Pole

Leveraging Economic Development for the Future; DC

Related

This amazing software and associated patents were birthed from within the organic ecosystem — and will assist in transforming remote collaboration and education.

Inspire Me Video Collaboration